In April I went on a Global Awareness Through Experience, {GATE} trip to Venezuela. On this page you will find page and stories from this experience. GATE is planning another trip to Venezeula next Janruary.

Introduction

Two years ago last April I traveled to Guatemala with a group from GATE (Global Awareness through Experience). It was a cultural experience which I recounted in a pictorial diary called Buried in Guatemala. The name came from my experience on Good Friday in Antigua, Guatemala. It was the major holiday of the year although the event it celebrated was honoring the death of Jesus on the cross. The people of Guatemala find real joy in this day of sorrow. The death and burial of Jesus gave the indigenous people of Guatemala real hope of finding new life.

This last April I traveled again with GATE. This time it was to Venezuela to experience the culture and people. Again I took pictures and notes. I was intending to write another pictorial journal of my experiences. However, in Venezuela the hope was not found in suffering and death but in the socialist or Bolivarian revolution that had happened and was happening in Venezuela. Thus the diary of this page is called Risen in Venezuela. Also the pictorial diary format did not seem right. The pictures told the story more than the words. So I decided to present pictures, in no particular chronological order, with brief stories with each picture to tell the story of the people and country. I will invite my fellow travelers to include pictures or reflections.

Now I can See!

ChuyOn the bus ride to the home of our guide, Lisa Sullivan, in the agricultural state of Lara, Lisa told us about some of her neighbors we would be meeting that evening. One was a young man she had met after he had gone blind. He had joined her music group of youth as something he could do to brighten his spirits. The Bolivarian Revolution in Cuba had brought in thousands of Cuban doctors and hundreds of health clinics for all, not just the rich. This young man had gone to one of these clinics and after an operation in Cuba he could see. The first time he saw her after his sight was restored he immediately recognized her and thanked her for what she had done for him.

When we got to Lisa’s house, with a beautiful view from the mountain, many of her neighbors were waiting for us on her porch. There was a group of three young men drinking beer and having a good time. I joined them and although I could not speak Spanish and they could not speak English we had a good conversation. When it became time for the neighbors to speak to our group from Canada and America, one of the persons in this fun-loving group of 3, Chuy, rose. He was the man who was blind and now could see. He told how he had served his country in the military and returned home only to become blind. He had become very depressed and struggled with his handicap. He took up craft-making as something he could do, and had joined the local music group. After the revolution, when the doctors from Cuba came to Venezuela to serve the people, they examined him and thought his blindness might be reversible. They sent him on an expense-free trip to Cuba where other doctors examined him and operated on him. He was blind and now can see, thanks to the Bolivarian revolution in Venezuela that has brought good, free health care to all. Chuy’s story is one of the many stories we heard of how the people of Venezuela, when the government starting to serve the common good, benefited.

In the picture here, Chuy is wearing an Atlanta Braves hat. It was given to him by one of the people in the group. Chury gave this man the bracelet off his wrist, one that he had crafted when he was blind. “I was blind and now I can see.”

Children of San Felix

Children of San FelizOn April 10th we met with government officials in Carora, a model city of the ‘bottom up’ constitutional process being implemented in Venezuela. In the afternoon we traveled to one of the isolated villages in the area, San Felix. The bus drove on a newly constructed dirt road, but we still needed to depart the bus at points where the road dipped to allow water to flow past it. Without the 30 of us Canadians and Americans, the bus was much lighter. Finally we reached this deserted village in the middle of nowhere in a very dry area with clay ground. I guess we were only the second group to visit this remote village, the first having been taken there by our guide, Lisa, a few weeks earlier. It turns out that one of the village leaders had been with us since our visit to the city hall in Carona. He took us to a newly constructed preschool. There the small children were waiting for us with a song they had learned in English. After some more songs and picture-taking, the leader of the village told us the story of the village. Before the Bolivarian revolution the government had ignored this village for forty

Church without a priestyears. They survived on basic substance of making bricks and raising goats. The present government had asked them to form a community council, which they did, and to make a proposal for funding, which they did. They asked for the funding for a church, the preschool where we were, and a few other things. Their proposal was granted and the funds were rewarded directly to the village and community council, no bureaucratic channels or agencies to deal with. The preschool is in daily use, and although they have no priest they are proud of their new church.

We were joined by other children and adults and taken on a tour of the village. During the walk I formed a special bond with the children with my silliness. I kept slapping my hand on my head, in what I consider the international sign of children. They thought it was silly but they caught on and started to do it. Again without understanding each other’s language we were having a lot of fun.

Making BricksWe saw the ancient way of making bricks, how they are created and fired in the oven in the ground. They said they would be making some changes in the way they make the bricks. For example kerosene for the oven, which is plentiful in this land of oil, would soon replace wood, which is scarce in this deserted area.

Goats of San FelixWe saw the heard of goats that, besides making bricks, forms the other part of their economy. Goats, which produce milk, meat and cheese, are plentiful through-out Venezuela. On the walk we noticed large holes with water at a low level. These are the reservoirs they have built to catch the rain during the rainy season. This muddy water is used for almost everything except drinking. With the lack of wells, drinking water must be trucked into the village.

Doing the ‘hokey pokey’When we got back to the school the children sang some more songs and then asked us to sing them a song. We all looked at each other, bewildered by what we all would know and they would enjoy. Suddenly Pastor Bill, a retired minister, stepped forward with a song he had used over many years with children at summer camp. It was the ‘hokey pokey’. A group started to do the hokey pokey song and actions and soon the children got it and joined us. It was a lot of fun and they wanted to do it repeatedly. Actually the ‘hokey pokey’ became our theme song, and we did it again for adults and children at the gathering at Lisa’s house near the end of the trip.

For many of us this visit at San Felix was the highlight of our journey. That evening I wrote in my diary “Today the children’s faces in this remote village were alight with joy of our visit, the silliness of Uncle Bob, the fascination of digital cameras and with the hokey pokey. They knew the international children symbol of putting your hand to your head and thought it was funny.”

In a ‘bottom up” society, this isolated small village of San Felix is important, and the children of San Felix are our top.

Simón Bolívar 1783–1830, Revolutionary and Educator

Simón BolívarBefore the GATE trip to Venezuela I had heard of Simón Bolívar but did not know much of who he was or of his legacy in South America. In Venezuela there were pictures and statues of him everywhere. Every city and village had a main plaza named after him. In Venezuela I learned that Bolívar’s legacy contributed decisively to the independence of present-day Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Panamá, Perú and Venezuela. I discovered he was born and died in Caracas, Venezuela. He liberated the land of these six countries from Spain and was the first president in 1821 of this new federation called Gran Colombia. It was counted alongside Mexico and the US as one of the three leading powers during the liberation years of the Americas. At various times, Simón Bolívar was president of the states of Venezuela, Colombia, Bolivia and Perú. His dream was to create an American Revolution-style federation between all the newly independent republics, with a government ideally set-up solely to recognize and uphold individual rights. However, eventually his dream had to succumb to the pressures of particular interests throughout the region, which rejected that model and allegedly had little or no allegiance to his liberal principles. He had to resign his presidency in April 1830, and died in disgrace the same year. However, his legacy lives on in various movements expressions of ‘Bolivarianism’, which is strongly endorsed in Venezuela. Hugo Chávez, th president of Venezuela, considers the socialist revolution now going on in Venezuela as following in the spirit of Simón Bolívar.

New School in VenezuelaAll the revolutionary reforms in Venezuela in health, government, and education are considered “missions” and have various names. Many of them are named after Simón Bolívar, especially in education. After I returned from Venezuela I looked up Simón Bolívar in Wikipedia, and one of the quotes attributed to Simón Bolívar explains why. He was a firm believer in education for all. “Nations will march towards the apex of their greatness at the same pace as their education. Nations will soar if their education soars; they will regress if it regresses. Nations will fall and sink in darkness if education is corrupted or completely abandoned.” (Simón Bolívar). Everyone in the city, barrio and village, young and old, male and female, is going to school. The Bolivarian Revolution continues in Venezuela, now with Hugo Chavez as president, but built on education for all.

Worm Guy

Worm GuyWhen our Venezuelan-American guide Lisa learned of my interest in vermicomposting use of worms for growing food, she said I had to meet the “worm guy” in her agriculture area, Palo Verde in the state of Lara. I had that chance when we went to dinner at Lisa’s house and her neighbors and friends were present. Lisa called me over to meet this farmer, Pedro Segundo Garcia. He is more commonly known by his nickname, Polilla, which means termite (he liked to chew wood when he was a kid]. He was there with his wife and family. He told us the story of how he got into organic farming and vermicomposting many years ago, before it was popular and many persons in Venezuela knew anything about this way of farming. His reason was, at first, strictly for health. He had some health problems and when he was tested it was discovered he tested positive for chemicals he used in farming. He had his wife and daughter tested and they too show signs of this chemical poising. So for health reasons he turned to vermicomposting, which is really an ancient system of agriculture with a high yield by use of worm castings and without the use of fertilizers.

Now many years later, after the recent Bolivian revolution and with the ‘bottom up’ government, there is a lot of interest in this way of agriculture using worms, sometimes called vermiculture. I asked him how big his worm-enriched compost pile was and he point to Lisa house. He said it was about that size. He and his family are now in good health and making a living by producing affordable, organic food. In Venezuela there is openness to new or old ideas which time has come around. Vermicomposting, for a culture that values health and human dignity of every citizen, is certainly the right idea at the right time. While I am an urban gardener he is a rural farmer. What he grows on a large scale I grow on a very small scale. However, we both have in common worms as livestock that make our soil organically rich. Polilla made me proud to be called a “worm guy”.

Music Everywhere for Everyone

One warm day we traveled by bus from an area of cacao plantations back through Caracas to the town of Barquisimeto. It was a long day and when we got to our hotel we were tired and hungry. But we were told to just drop off our bags and get back on the bus to a nearby barrio and the San Juan Cultural Center. One of our guides Lisa had raised her children in this barrio and had been part of the building of the cultural center. It was literally built by the sweat, labor and determination of the youth in the barrio without any government support. One of them, Leddy, was now on the bus with us as a guide. We heard the story from Lisa of how he was electrocuted and nearly died during the construction. The cultural center was built to provide two basic needs to the youth of the area, a library and place to study, and a cultural center for music.

Venezuela has a renowned music program for teaching how to play classical music to low-income youth. It is called “El Sistema” and it has existed for thirty years. Under the leadership of President Chavez and with state funding this program has grown and now reaches a quarter of million students and is making a impact on the world. One of its most famous graduates is conductor Gustavo Dudamel, who will head the L.A. Philharmonic Orchestra in 2009. He learned classical music in the same barrio that we were visiting. Lisa remembered hearing him play when he was only eleven years old and feeling chills down her spine from his music.

Although we were very late at arriving at the cultural center there were many young adults and youth of all ages waiting for us. They presented a performance of Afro-Venezuelan music and dance for us that raised our spirits and energized our tired bodies. At the cultural center they learn and practice all forms of music, but Afro-Venezuelan music and dance was just what we needed after a long day of travel. As in the US, Africans were brought to Venezuela as slaves for the plantations, were freed, and though now integrated into the society have kept their distinctive culture. As in Africa, the beat of the drum plays a large role in their music. Because of intermarriage of indigenous, Spanish and Africans in Venezuela it is hard to tell who is Afro-Venezuelan or not. Skin color in Venezuela, unlike the USA, does not play a major role. This music is distinctive and expressive of the Afro-Venezuela heritage.

The music and dance was very interactive and even got some of us tired visitors up and dancing. With all the music and dance we enjoyed we forgot how hungry and tired we were. But when the homemade chicken dinners did finally arrive (they had to send out to another barrio for such a large order) we all enjoyed with the youth a great meal.

Everywhere we went in Venezuela there was music, at a café for lunch, at our visit with the children of the San Feliz, on the streets, everywhere. Music powers the revolution. Music has healing powers and that night in the San Juan Cultural Center we were healed.

Sweet Cacao

Cacao podOur first journey outside of Caracas was to a Cacao plantation belonging to the Marquez family. How to use the Cacao plant to make a drink was discovered over 2000 years ago in the Pre-Columbian indigenous population. This drink was considered a special drink reserved for particular persons. The natives gave the drink to the Spaniards thinking they were gods. Eventually the Spaniards discovered the value of cacao and brought in slaves from Africa to work large cacao plantations. The Swiss put milk in the cacao making it what we call chocolate today. Venezuela became known as producing the best cacao in the world. However, with the end of slavery the large plantations were broken up.

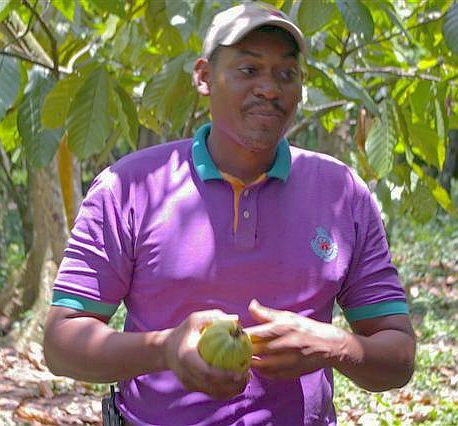

Javier MarquezOur host on the Marquez plantation was Javier Marquez, the great grandson of the original Afro-Venezuelan family that was given a small part of the plantation the family had served as salves. Before we could start the presentation he asked his Great Grandma, present, for her okay. She gave it. The Marquez family, five generations strong, lives and works on this plantation. They grow cacao, process it, run tours and have a small gift shop.

Black CaterpillarHe took us on a tour of the plantation showing us the cacao trees, small evergreen trees that produce the cacao pods. The main tool used to harvest cacao is a machete. The Cacao plant is organic, only needing the right climate and growing conditions. As with coffee trees, shade trees are grown next to cacao trees to protect them from the hot sun. When we were present there were many black caterpillars crawling around. Javier told us to be careful not to step on the caterpillars. The caterpillar appears only once a year during the season when the young cacao trees need sun. It climbs the shade tree and eats its leaves so that the sun will shine on the cacao tree. It then makes a cocoon to return the next year when they are needed. The caterpillar is a good example of the cycle of nature. Javier then showed us the traditional method of drying out the cacao and processing it.

Socialist Cacao ReineryWhile waiting for musicians and dinner to arrive we went to a nearby new socialist plant for cacao refining. This plant used modern technology to refine the cacao from the farmers in the co-op and send it to market. The plant was financed by the government but is run by co-op members like Marquez family who provide the cacao. This refinery allows the farmers to refine their own cacao and thus get full market value for their product.

After the tour we returned to the plantation for food, music and an opportunity to purchase chocolate from the Marquez family. Since it was early in the trip I did not buy much chocolate since it would have melted by the time we headed home. However, I found a bottle of Cacao liqueur, chocolate liquor, that we were able to sample before purchase. It was delicious. I still have some for special occasions.

The food and the music were good. We got introduced to a few new instruments used in Afro-Venezuelan music. Eventually it was time to go. We left with the sweet taste of cacao and an appreciation of the Afro-Venezuelan culture.