Email This Page

Many of my postings has been about the dilemma of treating mental health diseases. What can a parent or loved one do about an adult persons with a brain disease? This true story presents the question.

Schizophrenic. Killer. My Cousin.

—By Mac McClelland in Mother Jones Magazine May/June 2013 Issue

THE THING THAT STRUCK ME when I first met my cousin Houston was his size. He wasn’t much taller than me, if at all, and was slight of frame. On the other side of the visitors’ glass, he looked surprisingly small, young for his 22 years. The much more remarkable thing about him turned out to be his vocabulary, vast and lovely, lyrical almost—until it came to an agitated or distracted halt. In any case, all things considered, he seemed altogether extremely unlike a person who had recently murdered someone.

The symptoms displayed by Houston (in my family, a cousin of any degree is simply “a cousin”; technically, Houston is my third) in the year preceding this swift and horrific tragedy have since been classified as “a classic onset of schizophrenia.” At the time, it was just an alarming mystery. Houston had been attending Santa Rosa Junior College, living with his mom, playing guitar with his dad, when he became withdrawn and depressed. He slept all day; his band had broken up, and suddenly he had no friends.

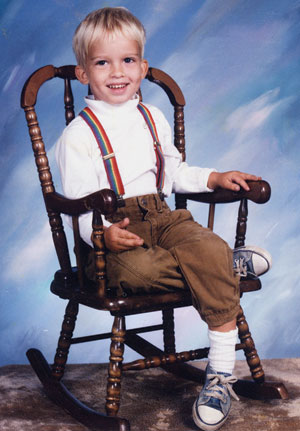

Mark with Houston at Houston’s

high school graduation in 2009 His dad, Mark, who had once struggled with depression and substance abuse but was now a pillar of the recovery community, and his mom, Marilyn, tried to help, took him to a psychiatrist. Houston didn’t have a drinking problem, but he mostly stopped drinking anyway. He didn’t smoke pot anymore, or even cigarettes. His psychiatrist indicated possible schizoaffective disorder in his notes, but put Houston on a changing regimen of antidepressants over the next eight months. It didn’t make any difference. Houston had started stealing his mom’s Adderall. He said it helped him feel better. He got fired from multiple jobs. Marilyn kicked him out, and he moved in with Mark.

“This was not my nephew,” my Aunt Annette, Mark’s sister, says of Houston’s behavior then. “He was always solicitous and loving and talkative with me. Now, he was anxious, quiet, said very strange things. He would say things that seemed not to come from him. I asked him how his therapy was going, and he said, ‘Terrible.’”

Toward the end of Houston’s devolution, he started having violent outbursts, breaking furniture; he tossed his mom across a room. Desperate now, Mark and Marilyn called the psychiatrist repeatedly and asked what to do. He told them to call the police.

“You can call the police,” the deputy director of Sonoma County’s National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), David France, said when I asked him what options are available to a parent whose adult child appears to be having a mental breakdown. “The police can activate resources,” like an emergency psych bed in a regular hospital, or transport and admission to a psychiatric hospital in a county that, unlike Sonoma, has one. But only if the police decide your child is a danger to himself or others can they arrest him with the right to hold him for three days—what in California is called a 5150, after the relevant section of state law. Otherwise you can be turned away for lack of space even if your loved one is willing to be admitted, or be left no good options if they’re not. Ninety-two percent of the patients in California’s state psych hospitals got there via the criminal-justice system.

But Mark didn’t want to call the police. For one, he didn’t think Houston was dangerous, just upset, despairing. Also, Mark read the news. The Santa Rosa cops had killed two mentally ill men they’d been called to intervene with in the last six years, one case resulting in a federal civil rights suit. This is not a problem unique to Santa Rosa—or to greater Sonoma County, which in 2009 paid a $1.75 million settlement to the family of a mentally ill 16-year-old whom sheriff’s deputies shot eight times. There’s no comprehensive data yet, but mental illness appears to be a factor in so many arrest-related deaths that the Justice Department has considered adding mental-health status to its national database of such deaths. Just last year, for example, the DOJ found the Portland, Oregon, police department had a “pattern or practice of using excessive force…against people with mental illness,” including eight shootings in 18 months and the beating to death of an unarmed man in 2006.

Anyway, Mark didn’t think three days of lockdown in a mental facility would make his son less unstable. He was looking for a meaningful treatment plan, not to rustle Houston through emergency services. “All those kids get shot by the police,” he told Marilyn. “Just let me handle it.”

Houston in pre-school.So Mark didn’t call the police, and Houston didn’t get any additional help. Ten days before all the really bad things happened, Annette came out to visit from Ohio. “Honey,” she said to her nephew, “something’s going on with you, babe. Either something’s happened to you, or you’re not sharing something. I’m really, really worried that something’s going on.” She says he turned his head and looked at her eerily and said, “Maybe I’ll tell you about it sometime.” She says, “It didn’t even sound like him.”

He did tell her about it, later. He told her he’d been having delusions, something about telepathic communications and aliens and wireless circuits. Something about his mom and dad—who’d been divorced for a long time—and teenage sister, Savannah, being in an incestuous sex ring. Something about an invisible friend, Devon, and also that he’d been cutting himself to exorcise the evil, and that Mark was poisoning him with lead and was the source of the evil. He did tell Annette, but only after it was too late, after he came home from the gym late one November night in 2011 and stabbed his father 60 times, with four different knives. When Savannah came downstairs and called 911, it appeared he was trying to behead him.

“What the FUCK?” my Aunt Annette exclaimed around the one-year anniversary of her brother’s death. “HOUSTON, what the FUCK?” But, she told me, the fact that what Houston did was “so heinous” didn’t mean he wasn’t a victim, too. “There was no facility, no support. There was nowhere to take him; there was nothing to do but call the police.”

“There’s been no place to put my anger,” she said about losing Mark. “Because I love this child. I know how sick he is. I was there at his birth.” And then she asked me to do the talking for a while, because she couldn’t talk anymore because she was sobbing.

Psychiatrist E. Fuller Torrey calls a crime like Houston’s “a predictable tragedy.” That’s what he has also called the Gabrielle Giffords shooting; he says the same thing about the Virginia Tech massacre, the Aurora movie theater shooting, the Sandy Hook Elementary shooting, and dozens of other recent homicides, some of them famous mass killings or subway platform shovings, but many of them less publicized. Ten percent of US homicides, he estimates based on an analysis of the relevant studies, are committed by the untreated severely mentally ill—like my schizophrenic cousin. And, he says: “I’m thinking that’s a conservative estimate.”

Saying that the severely mentally ill are disproportionately responsible for homicides has made Torrey, author of The Insanity Offense and the forthcoming American Psychosis, unpopular in some circles. “[My critics’] argument is you can’t talk about these things because it causes stigma,” he says. In the aftermath of the Newtown tragedy, some mental-illness advocates insisted that even if Adam Lanza had Asperger’s or any mental-health issues, it would be totally inappropriate to cite that as a factor in his actions. But other administrators and caretakers think it’s vital to bring up. “We have to think about mental-health care in a public health framework,” says Dee Roth, who is on the National Advisory Council of the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). “Public health measures solved rickets, cholera, people dying when they’re 30.” But when it comes to mental illness, she says, “we’re not treating the sick people.” And while the details of Lanza’s diagnosis or any attempts to treat it remain unconfirmed, what is known, as Torrey pointed out in a piece he coauthored in the Wall Street Journal, is that Connecticut is “among the worst states to seek such treatment. It has among the weakest involuntary treatment laws and is one of only six states that doesn’t have a law permitting court-ordered ‘assisted outpatient treatment,’” which, Torrey notes, “has been shown to decrease re-hospitalizations, incarcerations and, most importantly, episodes of violence among severely mentally ill individuals.” Although even Torrey, who founded the Treatment Advocacy Center, an organization that pushes for fewer restrictions on involuntary commitment, admits that such measures would hardly plug all the holes in our mental-health-care system.